Sick, Injured, Greyhounds Imprisoned and Bled Repeatedly for Veterinary Clinics in Asia

A PETA U.S. exposé of Hemopet, a canine “blood bank” in California, reveals that this so-called “rescue” warehouses approximately 200 greyhounds bred for and discarded by the racing industry in tiny crates and barren kennels for about 23 hours a day—even when they’re sick or they’ve been injured in fights with stressed kennelmates—and it boasts that it sells their blood to over 2,000 veterinary clinics in Asia and North America.

Barren Enclosures, No Room to Move Around

Hemopet kept many of the greyhounds in barren, rusty kennels. Others were locked in crates so small that they could barely turn around, stand up, stretch, or even see any other dogs.

These greyhounds—who, like all dogs, were eager to run and play and longed for companionship—were taken out of their cages only to be bled, walked briefly, or put in barren concrete-floored pens for a few minutes.

Tails Severed and Dangling

If you’ve ever donated blood, you probably sat on a cushioned chair and enjoyed some orange juice before heading home. But at Hemopet, greyhounds—who are intelligent, gentle, active dogs—were confined for about 23 hours a day, every day, on hard surfaces for months or even years. This perpetual imprisonment caused them to suffer from hair loss, calluses, and pockets of accumulated fluid under the skin.

Several dogs, desperate for attention and a respite from their near-constant confinement, sustained serious injuries when they wagged their tails enthusiastically against the metal wire of the enclosures. These injuries were sometimes so severe that they led to amputation, leaving dogs with just a stub of a tail. Staff said that it was “very common” for dogs’ tails to be injured. One staffer said that a Hemopet employee had broken a dog’s tail by shutting it in the kennel door and that it was “dangling by a little nerve … just a string.” Another staffer said that a coworker had approached her with a dog’s tail in his hand after a volunteer had severed it by shutting it in a door. Other dogs tore their nails or cut their paw pads on the metal cages.

Dogs ‘Pay Rent’ in Blood

Workers took the dogs’ blood every 10 to 14 days. This went on for 18 months or even longer, according to Hemopet staff. One employee said that workers even took blood from dogs with borderline anemia, a severe deficiency of the red blood cells needed to carry oxygen throughout the body, which is what critically ill or injured dogs often require when they receive blood.

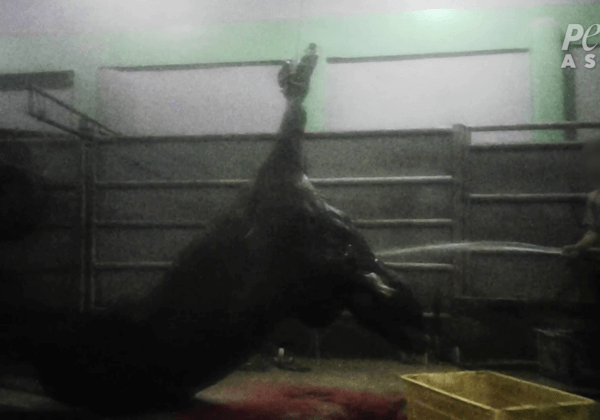

Stressed Dogs, Frequent Fights

Being deprived of exercise, companionship, and mental stimulation caused these dogs tremendous psychological distress, which led some to turn in frantic circles, paw desperately at their cage doors, and try to jump up even while inside the small crates. The frustrated dogs barked and howled ceaselessly, leaving all of them with no escape from the noise, which added to their chronic stress. The dogs’ stress was so pervasive that many of them suffered from diarrhea and loose stools.

Employees said that stressed dogs sometimes fought each other, resulting in torn ears, neck wounds, and bloody cages, but some were caged together even after fighting. One staffer said that she’d seen “some pretty gnarly neck injuries” at Hemopet, and another employee said that her hands were “covered with blood” when an agitated dog bit off part of another dog’s ear.

Despite taking in over US$1 million in blood product sales in 2016 alone from the dogs it obtains and bleeds, Hemopet keeps them in these substandard, desolate conditions.

What You Can Do

None of this suffering, stress, or deprivation is necessary. Many veterinary clinics help save sick and injured dogs’ lives by working with dog guardians who are willing to volunteer their large, calm, healthy dogs for occasional blood draws. These dogs get to go home to their comfortable lives afterward.

According to Dr. Linnaea Scott, a veterinarian with over 10 years of experience in emergency medicine, “In the case of a shortage, we find another way to help the anemic patient. We get the blood from the clients’ other Labrador, from the veterinary technician’s 80-lb. Rottweiler, or from any number of large dogs who will probably never donate ever again. … Veterinarians are resourceful and we will find another way” to obtain blood for transfusions besides relying on dogs imprisoned at blood banks [emphasis added].

Dr. Nicholas Dodman, canine behaviorist and professor emeritus at Tufts University’s Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, wrote, “These conditions … remind me of how farmed animals are intensively confined to produce meat, milk and eggs. To keep a dog lying in a crate, or muzzled in a kennel, with such limited space in prison-like conditions for 23 hours each day is unacceptable. … Animals donating blood should be kept in homes, not cages [emphasis added].”

Please, urge your veterinarian not to purchase blood from dogs held captive and to obtain blood only from dogs who get to live as all dogs should—in homes with loving families.